Table of Contents

Laryngoscopy Procedure Step By Step

laryngoscopy

Analyses the larynx and the back of the throat. Our vocal cords are located in our voice box, which also allows us to talk.

Laryngoscopy can be performed in various ways:

- Indirect laryngoscopy: At the back of the throat a mirror has been put. To see the throat region, the medical professional puts a light on the mirror. This process is straightforward. Most of the time, it can be completed while you are awake at the doctor’s office.

- Nasolaryngoscopy: A tiny flexible telescope is used in fiberoptic laryngoscopy, also known as nasolaryngoscopy. The throat and nose are both used to put the scope. The voice box is often checked in this way. For the procedure, the patient is awake. The nose will be sprayed with numbing medication. Usually, this process takes under a minute. It is also possible to do a laryngoscopy under a strobe light. The use of strobe lights can offer the provider more details regarding difficulties with your voice box.

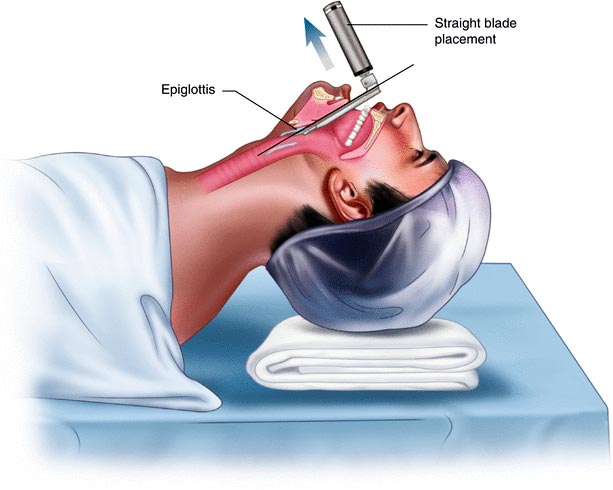

- Direct laryngoscopy: It is pushed into the back of your throat. The tube could be firm or flexible. With this treatment, the doctor can view farther down into the neck, remove an object, and take a sample of tissue for a biopsy.

Video Laryngoscopy (VL)

Video camera technology is used in video laryngoscopy (VL) to visualize airway features and make endotracheal intubation easier (ETI). With the development of video technology, more affordable, powerful, and dependable video laryngoscopes are becoming more widely available. The increased use of VL in patients with difficult airways or as a rescue device after unsuccessful intubation procedures has sparked its development.

VL has quickly established itself as a reliable tool in the toolbox of the anesthesiologist as well as other healthcare professionals (such as those working in the emergency room, intensive care unit, and prehospital settings) involved in airway management, despite the lack of conclusive evidence that VL increases overall ETI success.

Since the invention of video laryngoscopy, the approach to airway care has undergone a significant revolution (VL). Video laryngoscopes have swiftly become a common intubation tool in a range of clinical settings and circumstances, in the hands of both airway specialists and non-specialists. Their oblique perspective of the upper airway enhances glottic visibility, even when difficult intubation is suspected or actually encountered. However, further research is required to evaluate whether VL really does increase the success rates of direct laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation (ETI), intubation timeframes, and first-attempt success rates. Additionally, technological advancements have ushered in a wide variety of models, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Alternative approaches should be accessible, and these limits should be well known. As a result, the function of VL is still changing. Nevertheless, it is obvious VL broadens the armamentarium for all healthcare professionals and anesthesiologists who might be involved in airway management.

Direct Laryngoscopy (DL)

Glottic visualization is essential for managing airways in emergencies. If the vocal cords are visible during direct laryngoscopy (DL) (Cormack and Lehane [CL] grade I or II view. Success rates for intubations are very high. Intubation success is less likely, nevertheless, if the glottic aperture cannot be seen (CL grade III or IV). Even though only a small number of the difficult airway markers assumed to restrict DL access have been scientifically confirmed, using them together can nevertheless yield a respectable evaluation of expected airway difficulties. On the other hand, VL almost never fails to offer enough laryngeal visibility, although it might make it more challenging to implant indirect tubes.

Although there are techniques that allow that aim to cover both problematic direct and VL predictors, characterizing difficult VL predictors is not extensively explored, and the components are too broad to be clinically relevant (see discussion later). Similar to DL, sufficient video views are strongly connected with successful intubation, albeit the strength of this correlation can vary depending on the device and operator. Every patient should go through a standard approach for difficulty screening, regardless of whether DL or VL is intended. The mnemonic LEMON (Box 1.1), which we suggest using, has been demonstrated to have good sensitivity and high negative predictive value.

The most reliable procedure for securing the airway is still direct laryngoscopy (DL). It is a complex technical skill that requires training, experience, and frequent practice to develop and maintain. It also has a variable learning curve. For the best glottic visualization, DL needs a direct line of sight to align the airway axes (oral-pharyngeal-laryngeal). Head extension, neck flexion, and laryngeal manipulation, among other strenuous actions, are frequently used to realign these axes. To expose the glottis on a Macintosh DL, lifting forces of 35 to 50 N may be necessary. These airway manipulations have negative effects on the patient’s hemodynamics, cervical instability, oral and pharyngeal tissue destruction, and tooth erosion.

Advantages of video laryngoscopy

In comparison to DL, VL makes use of its camera to do indirect laryngoscopy, which eliminates the necessity for a direct line of sight to see the structures of the airways. In actuality, this enhances glottic visualization.

VL is less likely to trigger a stress reaction and cause local tissue damage since it applies less force (5–14 N) to the base of the tongue. Some video laryngoscopes cause less cervical movement than DL. In addition, regardless of whether a laryngoscopist is a rookie or an expert, there is a faster learning curve for DL than there is for DL. There is data that suggests longer intubation times with VL when compared to Macintosh DL, however, there is also data that shows equivalent or even shorter ETI timings.

In general, most VL devices have the following benefits: avoidance of the need to align the airway axes (oral-pharyngeal-laryngeal) to attain line of vision; improve glottic visualization, particularly in situations where mouth opening or neck mobility are restricted; higher success rate of ETI with non-expert, and possibly expert, laryngoscopists; ability for others to view the screen and help with ETI. For example, redirect cricoid pressure, acquire other airway devices.

Disadvantages of video laryngoscopy

Using VL devices has some drawbacks, including difficulty passing ETT despite improved glottic visualization; potentially longer intubation times; variable learning curves; potential weakening in development/maintenance of DL skill set, especially in those who are not airway management experts; potential for a false sense of security and lack of preparation for difficult airways; two-dimensional view with loss of depth perception; obscured view by fogging an airway, and potential for a false sense.

Difficult Direct Laryngoscopy

Look around outside

First, it’s crucial to examine the patient for any external signs of a difficult intubation, which can be found based solely on the clinical perception or initial gestalt of the incubator. For instance, a badly injured and bruised trauma patient immobilized in a cervical collar on a spine board should quickly invoke a consciousness of the difficulty to be anticipated. Subjective clinical judgment, which may be quite specific but insensitive, should be supplemented with other evaluations of whether the airway looks to be difficult.

Assess 3-3-2

To determine whether or not DL is appropriate as the second stage in the assessment of the difficult airway, the patient’s airway geometry is assessed.

To observe the glottis using a direct laryngoscope, the mouth must open wide enough. There must be space for the tongue in the submandibular region. The larynx must be positioned low enough in the neck to be seen. According to the 3-3-2 rule, the patient needs to be able to slip three of his or her fingers between the open incisors, with 3 of them on the lower jawbone’s surface beginning at the mentum. Two fingers from the prominence of the speech organ to the base of the chin. It is particularly challenging to cannulize a patient who has a high-riding cartilaginous structure and a receding lower jawbone because the operator cannot successfully pull the tongue out of the way. It overcomes the oblique angle for a direct read of the glottic aperture. The operator then performs the three tests, compares their finger size to the patient’s finger size, and completes the three stages.

Mallampati

A doctor can access oral using the Mallampati scale. When the tongue is placed on the hard palate, the oral pharynx may be visible, including the tonsillar pillars (class I), or it may be completely undetectable (class IV).

Classes I and II signify sufficient oral access, while classes III and IV represent, respectively, average difficulty and severe difficulty. According to a meta-analysis, the 4-class Mallampati score is an effective predictor of difficult laryngoscopy, but it is short as a standalone assessment tool. To finish the exam as intended and earn a Mallampati score, a patient must be awake and cooperative.

Obstruction or obesity

If the upper airway (supraglottic) is blocked, it may be impossible to see the glottis or do an intubation. Epiglottitis, head and neck malignancy, Ludwig angina, neck hematoma, glottic oedema, and glottic polyps are just a few of the conditions that can impair laryngoscopy, endotracheal tube passage, BMV, or all three. To complete this evaluation phase, examine the patient for airway obstruction and evaluate the patient’s voice. Obesity may not be a reliable indicator of difficult DL on its own, but it certainly makes other aspects of airway control more difficult. However, obese individuals typically have greater trouble being intubated than non-obese patients, thus preparations should take this into account in addition to the faster oxyhemoglobin desaturation and higher difficulties with ventilation when utilizing BMV or an EGD.

Neck flexibility

Any intubation technique including neck movement will help position the patient for the ideal DL.

To assess neck movement, the patient’s head and neck are flexed and extended across their full range of motion. Although the patient’s full sniffing motion gives the DL the best laryngeal image, neck extension is still the most crucial motion. Simple motion limitations have no impact on DL. However, a severe loss of motion, like that caused by rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis, may make DL impossible. Although DL is still successful in this patient population, cervical spine immobilization in trauma patients artificially reduces cervical spine movement.

Why Surec

The pulse of the world is accelerating, and so should the speed of your team's response.

Increase your patient safety level and save time with SUREC!

With SUREC you have everything you need to communicate with ED during an emergency or disaster, anywhere on Canada